NEW YORK — After he stopped a mentally ill Rikers Island inmate’s savage attack on a fellow detainee in November 2019, Correction Officer Charlie Bracey went home satisfied he’d saved a life.

Bracey had pulled Jorge Gutierrez off Sean McDermott as Gutierrez bashed McDermott 185 times with his cast-covered arm in a holding pen at the Anna M. Kross Center. “I reacted as quickly as possible ... I don’t see what I could have done differently,” Bracey told the Daily News.

But after the city paid the horribly injured detainee a $9 million legal settlement, Bracey nearly lost his job.

“Sometimes when the city pays, they want someone else to pay. And, they wanted it to be him,” his lawyer David Kirsch told a city administrative law judge who heard Bracey’s case and decided late in 2022 to restore him to his job.

Kirsch called the attack “an absolute systemic failure of Rikers Island” caused by understaffing.

“All Charlie Bracey did was save this inmate, who may have died that day. He should have been commended by the city,” Kirsch said.

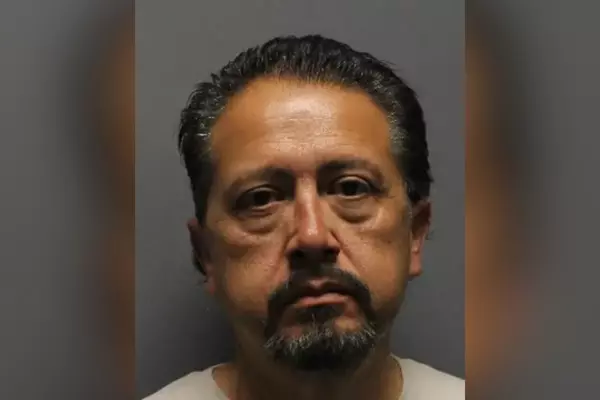

Bracey, now 53, went to work on Nov. 27, 2019, at the Kross Center, the largest Rikers Island jail, assigned to his usual “pre-screening” post, responsible for moving detainees held in two pens to their appointments at the medical clinic.

He learned there was no officer available to work as the “clinic expeditor” — a separate desk post which notifies detainees when it’s their turn to be escorted to their appointments, and keeps watch on the two holding pens. Gutierrez and McDermott were in one of those pens.

As he had done when he was assigned to the two separate posts, Bracey warned his boss, Capt. Mohammad Shanu.

Shanu told him to make do.

“There was always short staff in the facility and I advised Bracey do his best to cover both posts,” Shanu later testified at Bracey’s departmental trial.

Staffing problems gripped the Correction Department before the well-known worker absences and shortages that occurred during and after the Covid pandemic.

The number of uniformed DOC employees dropped 6% in the pre-pandemic years, from 10,862 in 2017 to 10,189 in 2019. But there were still about 2,250 more officers that year than detainees, figures published by the city Comptroller show. The average daily detainee population was 7,938 in 2019.

“We had a staffing shortage and I don’t think anyone realized how bad it was. People were resigning or retiring and there was a period where no classes went into the academy to replace them,” Bracey said.

“It was becoming a regular situation,” Bracey said in trial testimony. “The supervisors, at this point, were playing the odds. Eventually, something was going to go wrong. I knew something was going to go wrong eventually.”

As Bracey went about his tasks, Gutierrez started attacking McDermott in Holding Pen No. 2, hammering him in the head and face with the plaster cast covering his right arm, and slamming him into a metal railing.

Bracey was escorting detainees to the clinic and was not immediately aware of the attack, he testified. The clinic is a large area and there were walls and doors between where Bracey was and the holding pens, Kirsch said.

Over a minute into the assault, Bracey was walking past the pens to pick up another detainee and saw the attack in progress.

He pulled Gutierrez off of McDermott. Bracey said he didn’t think anyone would have stopped Gutierrez from attacking McDermott — but he believed his ”intervention would have been sooner had the clinic expeditor post been filled.”

Bracey heard nothing further about the incident until about a year later, in November 2020, when he was hit with several disciplinary charges for supposedly failing to respond to the attack.

It was not Bracey’s first time facing charges. In 2015, he was arrested for allegedly smuggling contraband when a multi-tool was found in his backpack. The Bronx DA’s office dropped the charges, but Bracey lost 15 compensatory days as a penalty in 2017. Bracey has said he left the tool in his pack by mistake.

McDermott’s lawyers sued the city in Manhattan Federal Court in February 2021, claiming Correction Department staff knowingly put the dangerous Gutierrez in the cell with McDermott and then failed to protect McDermott from the heinous attack, court records show.

Another year passed. On Feb. 22, 2022, during a pretrial conference in the disciplinary case over Gutierrez’s assault, the Correction Department offered Bracey a plea deal of 25 lost vacation days. He agreed to settle for 18 lost vacation days.

The deal was formally signed by Correction Department lawyers and then by the department’s deputy commissioner of trials.

Then it landed on the desk of Correction Commissioner Louis Molina.

In the meantime, on March 15, 2022, McDermott settled his lawsuit against the city for $9 million — one of the largest settlements of its kind in city history.

In April 2022, Molina rejected Bracey’s plea deal without written explanation and insisted Bracey should be fired.

For Bracey to save his job, he had to go to trial.

“They wanted to show they did something,” Bracey said. “But I’m the single breadwinner for my family. My wife had to give up her career in education to take care of my daughter. So, it was very stressful. You think you are about to lose your livelihood.”

Bracey’s trial before Jonathan Fogel, a judge for the city Office of Administrative Trials and Hearings, began Sept. 22 and continued on three dates in October and November.

“This is a real simple case. Can someone be in two places at the same time? I submit no. And that’s why this man is not guilty,” Kirsch said in his opening statement.

During the trial, the three Correction Department lawyers assigned the case relied on surveillance video of the incident and called just one witness, Jason Walker, city correction officer and investigator with six years on the job.

“Officer Bracey didn’t respond quick enough to stop the threat or stop inmate McDermott from being choked or, and/or assaulted,” Walker testified.

But in a key moment, Walker admitted he did not interview all responding officers or entirely understand the difference between the two posts, the trial transcript shows.

The case turned on an almost second-by-second analysis of the security video.

Correction Department lawyers said the beating went on for one minute and 17 seconds before Bracey intervened.

But Kirsch used the video to show that Bracey was able to intervene 29 seconds after he first noticed the attack “in the corner of his eye.”

Correction Department lawyer Nicole Tartak asserted in her closing statement Nov. 10 that Bracey delayed entering the cell and gave a half-hearted effort to pull the two men apart.

“What the court observed in that video is an officer who saw a deadly encounter and chose inaction. Period,” Tartak said.

But the judge sided with Kirsch’s assertion that Bracey acted in 29 seconds, not the more than a minute the Correction Department claimed.

In his closing, Kirsch called the Correction Department investigation “lazy and incompetent” and used an expletive to suggest the department was scapegoating Bracey after having to pay McDermott so many millions.

“I don’t want to curse — but this is case is a bunch of bulls—, is really what this case is,” Kirsch said in court. “That’s really the only way I know how to characterize it.”

Judge Fogel on Dec. 29 recommended dismissal of the charges.

“(Bracey’s) actions helped save McDermott’s life and prevented serious injury,” Fogel wrote. “Of the three officers present inside the cell, (Bracey) did the most to de-escalate the assault. … He is an experienced officer who used his best judgment in the moment.”

On Feb. 7, 2023, Molina signed off on Fogel’s decision without comment. No penalty was imposed — meaning that in the end, Bracey lost no vacation days or suffered any other punishment.

Correction Department officials did not respond to a series of questions centering on why Molina pursued Bracey’s firing.

No one else was charged nor were any officials held responsible for the staffing foul-up that gave Gutierrez the window to beat McDermott nearly to death and put Bracey’s career on ice for three years, Kirsch said.

Now free of the disciplinary case, Bracey works in the cashier’s office at the Kross Center as he waits to be brought back to work in the clinic where he was once posted.

“I felt very relieved. The decision showed how much the judge was paying attention to every word that was said. I felt I was treated fairly in the trial,” Bracey said.

———