As a Fulton county, Georgia, board of registration and elections meeting began in earnest on Thursday afternoon, the elections director, Nadine Williams, unfurled a prepared statement about a recent hack of county government computers.

“There is no indication that this event is related to the election process,” Williams said. “In an abundance of caution, Fulton county and the secretary of state’s respective technology systems were isolated from one another as part of the response efforts. We are working with our team to securely reconnect these systems as preparations for upcoming elections continue.”

Any time the Fulton county elections board meets, a cantankerous crowd greets them to pepper appointees with challenges to voter registrations or demands for paper ballots or generally unsympathetic noise. The rancor of the 2020 election and its unfounded charges of vote tampering still ripple through the democratic process. Elections officials in Fulton county take care about what they say, knowing that a platoon of critics lie waiting to pounce on a misplaced word.

Even by that standard, county officials have been holding uncharacteristically tightly to a prepared script – or saying nothing at all – in the days since a computer breach debilitated everything from the tax and water billing department to court records to phones.

“Because it’s under investigation, they’re telling me to stick to a list of talking points,” said the Fulton county commissioner Bridget Thorne. “The county attorney drafted them.”

She did say that the county had come under a ransomware attack – and that the county had not paid off the attacker. “We’re insured very well,” she said.

Systems began to fail on the weekend of 27 January. Ten days later, the phones for most departments returned a busy signal error when callers rang them up.

County officials either cannot or will not directly and completely answer important questions about the cyber-attack’s scope. The Fulton county chair Robb Pitts made a brief statement on 29 January about the hack without taking questions.

“At this time, we are not aware of any transfer of sensitive information about citizens or employees, but we will continue to look carefully at this issue,” Pitts said. “We want the public to be aware that we will keep them informed as additional information become available.”

County commissioners held an emergency meeting with only two hours’ notice on Thursday evening, ostensibly to discuss the cyber-attack. The commission immediately entered a closed executive session, emerging 90 minutes later to say nothing to reporters.

Asked whether leaders were aware whether sensitive personal information had been stolen by hackers, the county spokesperson refused to say.

The FBI is leading the investigation, with assistance from the Georgia bureau of investigation and Homeland Security’s cybersecurity and infrastructure security agency (CISA). An FBI spokesperson said the bureau had been in contact with Fulton county regarding the hack but could not comment on an active investigation.

If this were any other county, common concerns about whether residents’ or employees’ credit card data had been stolen and when water billing would resume would be at the forefront of conversations. But Fulton county is where political freight trains cross tracks. Fulton county, home to most of Atlanta, is the largest county in one of the US’s most contested swing states.

It is the subject of continuing litigation over the security of its election equipment in federal court.

Last year, Georgia replaced its creaky voter-registration system with the Georgia registered voter information system, or Garvis. The state built the system on a Salesforce base. Garvis complies with the FedRamp federal standard for cloud-computing security, according to the office’s statements.

A computer system that is FedRamp-compliant has monitoring safeguards to see whether unusual amounts of data are flowing out of storage servers – a telltale sign that hackers are stealing personally identifiable information.

When the elections division of the Georgia secretary of state’s office heard that Fulton county’s computers had been hacked, it first cut the county off from access to the state’s computers – and then shut everyone out of Garvis just to make sure the central system had been unaffected, said Mike Hassinger, a spokesperson for the state office. The state restored registration services to other counties within a day or two, after checking the logs to ensure nothing strange had taken place.

State elections officials asked the county to wipe their elections computers back to the baseline, which they have done, Hassinger said. Those computers are isolated from the rest of the network, he said.

“We are now back up and running on Garvis,” Williams, the Fulton county elections director, said on Thursday.

Fulton county, like every other county, is preparing for the next election: the presidential preference primary on 12 March. Registration for that contest ends next week.

There are no slow weeks in Atlanta. Fulton county is also where the former president Donald Trump faces criminal charges for attempting to tamper with the 2020 election. And the court’s creaky computer system is all the way down.

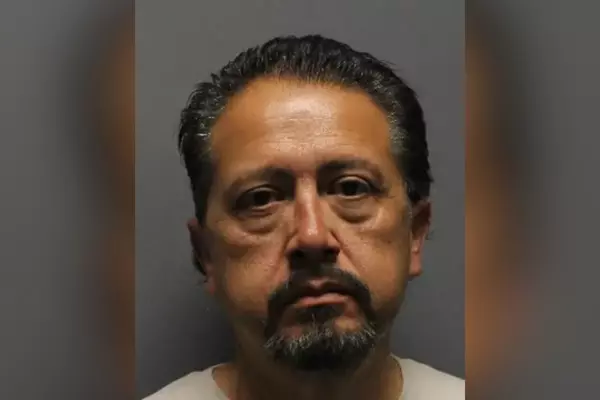

For example, this morning, after the high-profile arrest of an activist on Thursday on arson charges related to “Cop City” protests, the media engaged in a spirited argument with court and jail staff. Arraignments are usually done by Zoom meeting with a prisoner remaining at the jail.

But Zoom is offline. A judge was forced to trundle into Fulton county’s notorious jail to conduct the proceeding in person, yet the jail doesn’t allow visitors. Eventually, the sheriff relented and allowed some media representatives inside.

The hack didn’t target the district attorney’s office and will not affect the Trump case, said Jeff DiSantis, a spokesperson for the office. “All material related to the election case is kept in a separate, highly secure system that was not hacked and is designed to make any unauthorized access extremely difficult, if not impossible,” he said.

The office has yet to respond to questions about whether evidence stored on county computers in other criminal cases might have been compromised. Notably, the Atlanta police department said it isn’t accepting emails from Fulton county email addresses for the moment, just in case.

The county’s court, tax and financial systems have been particularly affected, said the county manager, Richard “Dick” Anderson. “Our teams have been working around the clock to understand the nature and scope of the incident,” Anderson said in a briefing before the county commission on 7 February. “While a number of our key systems have been affected by this outage, it’s important to note that we have no reason to believe that this incident is related to the election process or any other current events.”

Fulton county employs about 5,000 people. As of Wednesday, only 450 county phone lines were operable. The county cannot issue water bills or tax bills. For about 10 days, it could not hold property tax hearings.

The county’s internal human resources portal remains down, making it difficult to hire, to manage payroll or to schedule staff.

In public, the county has yet to say when it will fully restore services. Privately, officials are telling employees that functionality may not return before the end of the month.