In 1971, when Daniel Ellsberg arrived at a federal court in Boston, a journalist asked if he was concerned about the prospect of going to prison for leaking a 7,000-page top-secret history of the Vietnam War. Ellsberg responded with a question of his own: “Wouldn’t you go to prison to help end this war?”

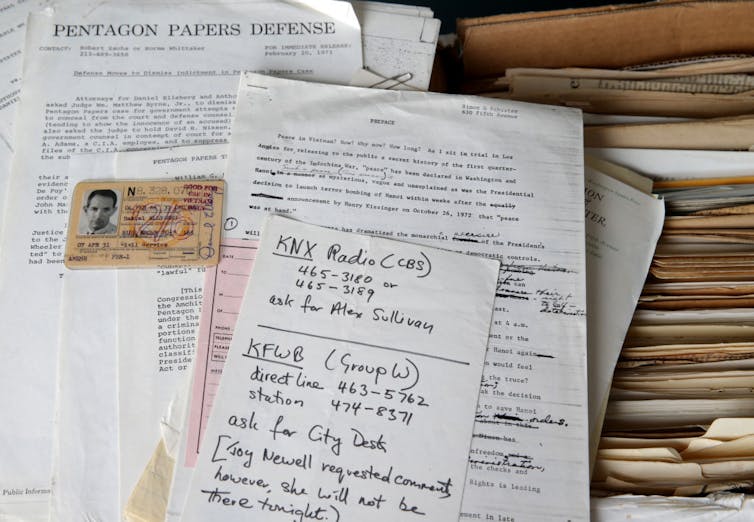

The classified documents Ellsberg released to The New York Times and 18 other newspapers were quickly dubbed the Pentagon Papers. They exposed more than two decades of government deceit about U.S. involvement in Vietnam, from 1945 to 1968.

To millions of Americans who opposed the war, Ellsberg’s whistleblowing was an act of patriotism, but millions of others regarded it as treason. In Ellsberg’s own papers at UMass Amherst, where I teach history and direct the Ellsberg Initiative for Peace and Democracy, you can read hundreds of letters to him from ordinary citizens expressing both extremes: the highest possible praise, and vitriolic, often antisemitic, hostility.

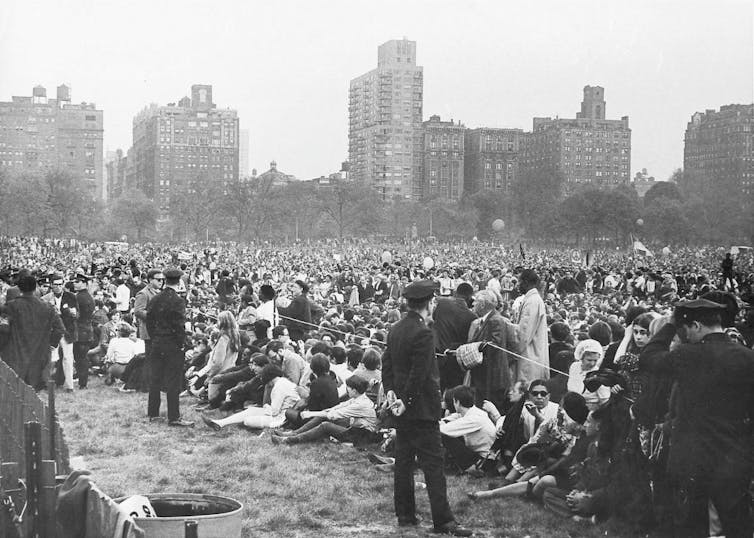

How a young war planner became a peace activist is one of the most striking conversion stories in American history. But Ellsberg’s political and moral transformation did not happen in a vacuum. It reflected a titanic shift in public attitudes about the Vietnam War. The massive anti-war movement inspired and reinforced Ellsberg’s dissent – and, in turn, his example has emboldened activists and whistleblowers in the decades since.

A ‘knightly calling’

Once a fervent Cold Warrior, Ellsberg joined the Marine Corps in the mid-1950s, earned his doctorate in economics from Harvard and in 1959 became a nuclear war analyst for the Rand Corp., a think tank that, at the time, was funded mostly by the Air Force. In 1964, he was one of the brainy young analysts, dubbed “whiz kids” by the media, that Defense Secretary Robert McNamara recruited to the Pentagon.

Throughout his 20s and early 30s, Ellsberg believed that serving the president was a “knightly calling,” even if it required lying to the public. So how did he come to believe that loyalty to truth-telling superseded loyalty to the chief of state?

From 1965 to 1967, Ellsberg went to Vietnam for the State Department, believing the war was a challenging but necessary part of a global struggle to contain communism. Yet he became deeply disillusioned, convinced that the war could not be won. He was particularly disturbed by indiscriminate U.S. bombing and shelling, most of it on South Vietnam, the land the U.S. claimed to be protecting. About 20,000 American lives had already been lost, and roughly a million Vietnamese people had been killed, about half of them civilians. By the war’s end eight years later, 58,000 Americans and 3 million Vietnamese had died.

Pivotal moments

By 1968, Ellsberg was trying to persuade U.S. leaders to seek a negotiated end to the war. On his own time, meanwhile, he was beginning to meet anti-war activists who advocated a bottom-up effort to demand immediate U.S. withdrawal.

One of them, a Gandhian pacifist named Janaki Natarajan, convinced Ellsberg that he should study leading advocates of nonviolent resistance, such as Martin Luther King Jr., Henry David Thoreau and Barbara Deming. To this day, one of Ellsberg’s favorite quotations comes from Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience”: “Cast your whole vote, not a strip of paper merely, but your whole influence.”

But most galvanizing for Ellsberg were the Pentagon Papers, which he helped compile for McNamara. Full of technocratic euphemisms for lethal policies, the documents convinced him that the entire history of U.S. involvement in Vietnam was marked by deception: that it was an aggressive counterrevolution that denied the Vietnamese people the right of self-determination, disguised as a battle for democracy.

Ellsberg had first viewed the Vietnam War as a just cause to be won, then as an unwinnable stalemate to be gradually abandoned. By late 1969, however, he saw it as an immoral war to be ended unilaterally and immediately.

Millions of Americans had already come to that conclusion. Back in 1965, in fact, Ellsberg’s future wife, Patricia Marx, agreed to a first date only if it included an anti-war demonstration in Washington.

Just as he finished reading the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg attended a War Resisters League conference that proved pivotal to his decision to leak the documents. There he met a few of the 3,250 young Americans who were sentenced to up to three years in prison for resisting the draft. Deeply moved by their courage, Ellsberg asked himself what he could do if he were willing to risk prison and his career.

A month later, with help from his friend and Rand colleague Anthony Russo, Ellsberg began photocopying the Pentagon Papers.

Going public

For the next year and a half, Ellsberg tried to get anti-war members of Congress to put the documents into the congressional record and hold hearings. None was willing, so he eventually offered them to war correspondent Neil Sheehan at The New York Times – the first newspaper to report on the papers’ revelations.

Public interest was scant, however, until President Richard Nixon began attacking the press and Ellsberg. Although the Pentagon Papers did not include Nixon’s time in office, the White House feared that Ellsberg might leak more documents – especially about Nixon’s 1968 effort to sabotage the Vietnam peace talks to improve his odds of winning the presidential election.

The government indicted Ellsberg on a dozen felony counts with a possible 115-year prison sentence. He was the first American ever criminally charged under the Espionage Act of 1917 for disclosing classified documents to the press and public rather than to a foreign agent or nation.

Ellsberg was spared prison. Late in his 1973 trial, Watergate prosecutors discovered that the White House had authorized crimes against him, including a break-in at his psychiatrist’s office, in a failed search for incriminating information. The judge had little choice but to declare a mistrial.

Post-Papers life

Ellsberg was a free man, but the personal cost of his dissent was severe. He lost many friends and had to forge a new career as a writer and lecturer. For more than five decades he has been a activist and has been arrested for nonviolent civil disobedience some 80 times on behalf of peace, nuclear disarmament, government accountability and First Amendment rights.

To most government insiders, Ellsberg’s mutiny was an unpardonable breach of the national security state. No one with so much access to power and privileged information in the U.S. government has ever broken so radically with the policies they once supported.

Yet 50 years later, Ellsberg is widely lauded, even by many people critical of the younger whistleblowers he has inspired and defended. Since Sept. 11, 2001, more than a dozen other people have faced criminal charges under the Espionage Act, and some – including Jeffrey Sterling, Chelsea Manning, Daniel Hale and Reality Winner – have been incarcerated.

In early March 2023, Ellsberg made public a letter to friends and supporters announcing that he has terminal cancer with only months to live. He closed by thanking fellow activists whose “dedication, courage, and determination to act have inspired and sustained my own efforts.”

Ellsberg’s life and legacy are reminders that individual acts of moral courage depend on examples set by others, and they have the potential to spark more, far into the future. As Ellsberg often says, “civil courage is contagious.”

Christian Appy is the director of the Ellsberg Initiative for Peace and Democracy at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. He is currently writing a biography of Ellsberg.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.